The shape of a music library

Most music libraries fail because they stop reflecting how their owner thinks of music. Folders stop scaling, playlists start lying. At some point, you realize you’re no longer navigating your collection — you’re working around it. This is a personal story of how organization became a creative tool.

There are many ways people organize their music: strict folder hierarchies, carefully named files, manually curated playlists, smart playlists, tags, ratings, or some hybrid of all these. Each approach has its own strengths and tradeoffs.

This post is however not an attempt to catalogue or evaluate every possible method. Instead, it explains how I personally organize music, how that approach evolved over time, and why it continues to work for me after decades of collecting, listening as a music lover, and performing as a DJ.

Evolution of music organization

My journey started with folders. In the early 2000s, I was building PCs, running Windows, and trying different music players over time. Out of the many, only two really stuck: Winamp and Sonique (the latter was a short‑lived love affair that I can remember fondly decades later).

Regardless of which player I was using at the time, organization was almost entirely file‑system driven. On Windows, everything is treated as a file. This is a fundamental mental model shaped by the Microsoft ecosystem: a file is conceptually almost equivalent to its contents for the ordinary user. You had directories, subdirectories, and filenames. There were higher‑level abstractions for music ― most notably the M3U format, which emerged to manage playlists and step beyond the constraints of a single directory. Winamp could open and manage these files, but it did not provide a true model for organizing a music collection. If you wanted structure, you built and maintained it yourself. That meant carefully naming folders, keeping hierarchies consistent, and manually updating playlists. In practice, very few people maintained large numbers of M3U files in a disciplined way. The burden was high, and the tooling did not really support music as a living, evolving collection.

In 2007, when I left Budapest to work for Last.fm in London, I was given a Mac for the first time and started using iTunes. This was a fundamental shift. In iTunes, the physical placement of files became largely irrelevant. Music was treated as a first‑class entity. The sidebar invited you to think in terms of playlists rather than folders. You no longer asked, “Where is this file stored?” but rather, “How do I want to experience this music?”

Smart playlists encourage creativity

In 2002, Apple introduced smart playlists with iTunes 3 as part of Mac OS X Puma (version 10.1). This was a quiet but fundamental shift in how personal music libraries could be managed. Instead of manually curating playlists track by track, users could define rules based on metadata such as genre, artist, rating, play count, date added, or even whether a track had been played recently. iTunes would then continuously evaluate the entire library and keep these playlists up to date automatically. For the first time, playlists became living views over a collection rather than static lists frozen in time.

Origins of rule-based playlists in music software

Apple announced by Smart Playlist features as part of iTunes 2 on July 17, 2002 which back then required Mac OS X 10.1.4 (Puma).

Smart Playlists in iTunes automatically updated based on user-defined rules. Whilst iTunes was among the first mainstream music players to offer rule-based playlists, it is currently unknown to me whether it was an absolute first.

Microsoft Windows Media Player 9 Series (announced Sept 3, 2002) also introduced “Auto Playlists” described as “intelligent music mix management,” i.e., dynamically/automatically created mixes from the library.

If you know more how this feature has been introduced to the public, please reach out to me via one of the social media channels listed in the bottom of this site and let me know.

Smart playlists allow you to define rules over your entire collection: genre, rating, play count, date added, BPM, comments, and many other attributes. These rules could be combined, and the resulting playlists updated automatically as your library changed. This eliminated a major source of friction. You no longer had to remember to add tracks to multiple playlists. If a track matched the criteria, it appeared. Organization became declarative rather than manual. Smart playlists were not just a convenience for me; later they have become essential. I have been running weekly radio shows for over 20 years, and have been DJing for live audiences for just as long. In those contexts, speed, recall, and freedom of choice matter enormously.

Many DJs prepare maybe a hundred tracks for a given show or gig, constrained by the size of a USB stick. I never adopted that model and I never intend to. I find it creatively limiting. There are few worse experiences than thinking of the perfect track during an immersive mix, only to realize you don’t have access to it. It breaks the flow and quite frankly it takes away a small piece of my soul with it. For that reason, I have always taken my laptop and my entire collection with me. This means full freedom of choice during performances and listening on the go. It’s liberating. However, carrying your entire library is only useful if you can navigate it effectively.

Building an immersive listening experience is about selection, sequencing, and maintaining quality over time without unnecessary repetition. Smart playlists became the backbone of that process.

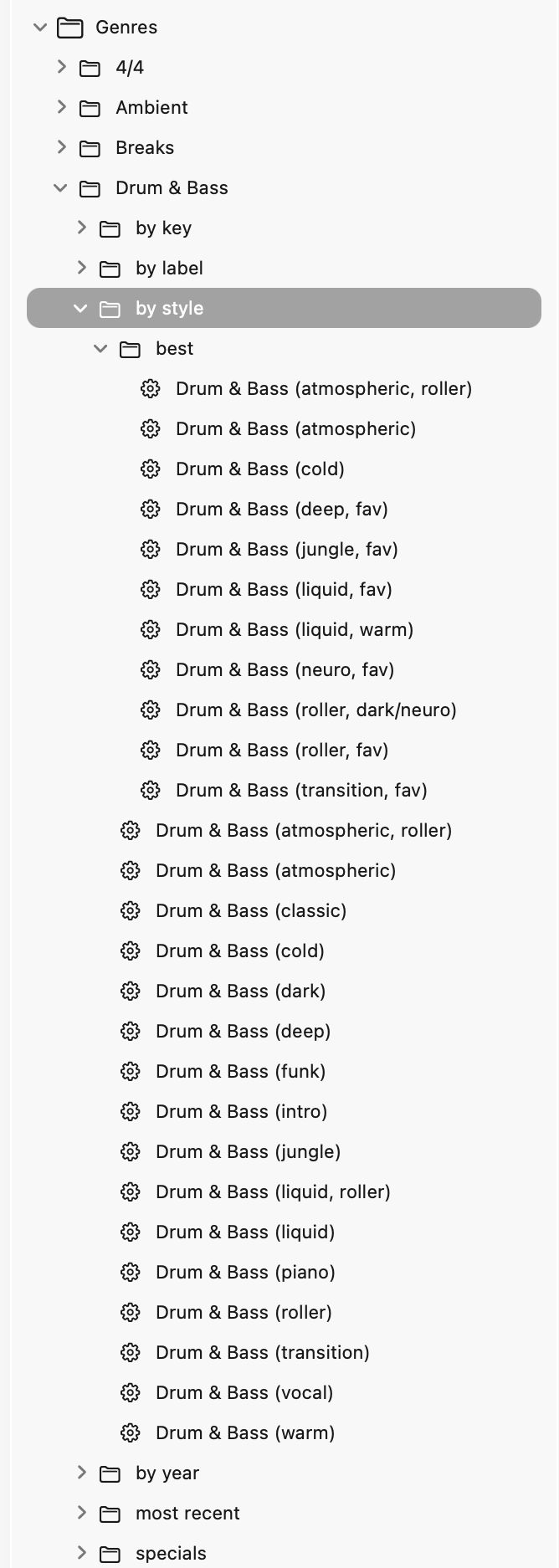

I started by creating smart playlists for the most common types of tracks I needed during my radio shows. While running a drum & bass focussed radio show, I separated sub‑genres into distinct playlists: liquid funk, jungle, neurofunk, and so on. This made stylistic shifts deliberate rather than accidental.

What are these sub-genres you are talking about?

Liquid funk emphasizes musicality and emotion, pairing rolling breakbeats with warm basslines, jazz-influenced chords, and soulful vocals, as heard in the work of Calibre, High Contrast, and Netsky.

Jungle is the raw, early form of drum and bass, driven by chopped breakbeats, reggae and dancehall influences, and an energetic, rough-edged sound exemplified by Goldie, Shy FX, and Roni Size.

Neurofunk focuses on dark, futuristic atmospheres and intricate, heavily processed bass design, prioritizing technical precision and intensity, as defined by artists like Noisia, Ed Rush & Optical, and Black Sun Empire.

Jump-up is built around simple, exaggerated bass riffs and high-impact drops designed for immediate crowd reaction, a style popularized by producers such as DJ Hazard, Macky Gee, and Bou.

Techstep represents a colder, more mechanical evolution from jungle, emphasizing minimalism and dystopian moods, and laid the groundwork for neurofunk through figures like Kemal, Dom & Roland and Ed Rush & Optical.

Atmospheric (or intelligent) drum and bass prioritizes space, texture, and ambience over aggression, creating immersive listening experiences often associated with pioneers such as LTJ Bukem and Blu Mar Ten.

I created dedicated smart playlists for special cases too. Choosing an opening track, for example, is disproportionately important. Great intros are often long, atmospheric, and easy to forget when your collection spans decades. To solve this, I created a dedicated smart playlist for tracks with strong intros. I have smart playlists for intros (and outros), vocal and instrumental tracks, or the biggest party bangers my library has ever seen or tunes for the moody wintertime.

As my collection and habits evolved, so did the playlists themselves. Some were split, some had been merged, and some became obsolete and were removed entirely. One particularly powerful pattern emerged from combining smart playlists. By intersecting rules, I could build higher‑level filters efficiently. For example, combining a playlist for “warm drum & bass” with another for “music added in the last two weeks” gave me instant access to fresh tracks suitable for the opening section of a show.

I maintain playlists for concepts such as “atmospheric”, “cold”, “warm”, “roller”, or “minimalist”. Music, however, is complex. A single track can be atmospheric and “cold” at the same time, other times “warm” as well as a high-energy roller. Smart playlists handle this naturally. A track can appear in multiple contexts without manual effort. Over the years, I have built many combinations, and they have served me remarkably well.

The million ways to relate to music

A part of my organization depends heavily on metadata (based on release year or music label for example) whilst the rest gradually converged around mood. Other people prefer carefully curated directory hierarchies and quite frankly I don’t blame them. They have invested years into a system that works for them. Well‑named folders provide a sense of order and control, and for many music hoarders that is entirely sufficient. It’s even beautiful.

Ultimately, organizing music is a deeply personal act.

It reflects how you relate to it: whether you see it as files, albums, moods, tools for performance, or companions for specific moments.

From a product perspective, there is an inherent tension here: Constraints lower the barrier to entry. They make applications simpler, faster, and easier to understand or reason about. But flexibility enables mastery. The more expressive the system, the more it can adapt to serious, long‑term use ― at the cost of increased complexity in both code and user interface. More options mean more screens, controls, and concepts. This complexity has to live somewhere.

The goal, for me, is to find the sweet spot between these extremes: keeping the interface simple and intuitive so that Audiqa feels easy and delightful, while ensuring it remains powerful enough for serious music lovers who want to grow into it over time.

If you want to follow the process behind the development of Audiqa you can subscribe to updates via a standard RSS feed or the low-traffic Bluesky and Twitter profiles.